Welcome back to our exploration of Intensity Transformations. This post is a continuation of our previous discussion, where we covered the general introduction, some auxiliary functions, Gamma Transformation, and Log Transformation. If you haven't read the first part yet, I highly recommend you start here to understand the foundational concepts. In this post, we focus on the Contrast-Stretching and Threshold transformations.

Contrast-Stretching Transformations

As the name suggests, the Contrast-Stretching technique aims to enhance the contrast in an image by stretching its intensity values to span the entire dynamic range. It expands a narrow range of input levels into a wide (stretched) range of output levels, resulting in an image with higher contrast.

The commonly used formula for the Contrast-Stretching Transformation is:

\begin{equation*} s = \frac{1}{1 + \left( \dfrac{m}{r} \right)^E} \end{equation*}

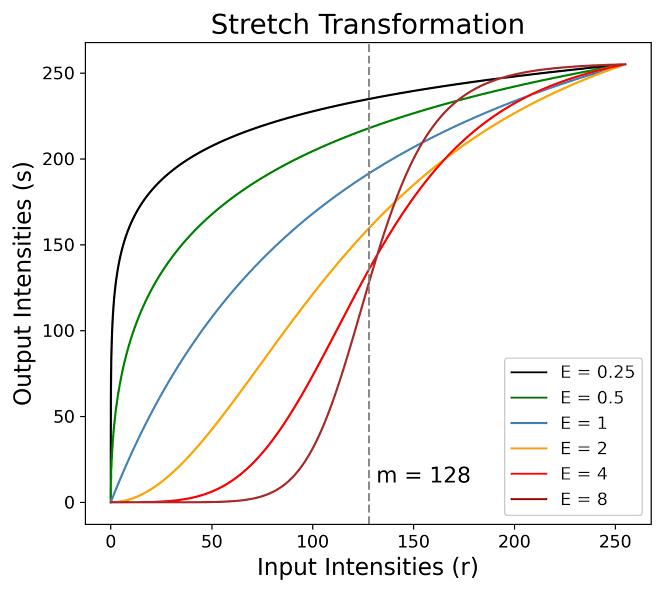

In this equation, $m$ denotates the intensity value around which the stretching is centered, and $E$ controls the slope of the function. Below is a graphical representation of the curves generated using different values of $E$:

These curves illustrate how varying $E$ affects the contrast-stretching process. A higher value of $E$ results in a steeper curve, leading to more pronounced contrast enhancement around the intensity level $m$, darkening the intensity levels below $m$ and brightening the levels above it.

Python Implementation

We now introduce a practical implementation with the stretch_transformation function. This function applies the stretch transformation to an image, enhancing its contrast by expanding the intensity values.

# Function to apply the Stretch Transformation

def stretch_transformation(Img, m = 128, E = 4):

# Apply the Stretch transformation formula

s = 1 / (1 + (m / Img)**E )

# Scale the transformed image to the range of 0-255 and convert to uint8

Img_transformed = np.array(scaling(s, 0, 255), dtype = np.uint8)

return Img_transformed

The function first applies the Stretch Transformation formula to the input image. After the transformation, it employs the scaling function to scale the transformed pixel values back to the range of 0-255. Finally, the transformed image is converted to an 8-bit unsigned integer format (np.uint8).

Having explored the concept of Contrast-Stretching transformations, we can apply this technique to a real image using the following code:

# Load an image in grayscale

Im3 = cv2.imread('/content/Image_3.png', cv2.IMREAD_GRAYSCALE)

# Apply the Stretch transformation

Im3_transformed = stretch_transformation(Im3, m = 60, E = 1)

# Prepare images for display

images = [Im3, Im3_transformed]

titles = ['Original Image', 'Stretching Transformation']

# Use the plot_images function to display the original and transformed images

plot_images(images, titles, 1, 2, (10, 7))

We first load an image in grayscale from a specified path (/content/Image_3.png). We then apply the Stretch Transformation with a midpoint $m = 60$ and a slope $E = 1$. We finally apply the plot_images function to display the original and transformed images. The results are shown below:

In the original image, the details and bones of the skeleton are discernible only in certain regions. Particularly, the lower and upper extremities are barely visible, obscured by the limited contrast of the image. However, the transformed image presents a stark contrast. The details are noticeably more visible. This enhanced visibility is a direct result of the stretching transformation, which has effectively expanded the range of intensity values.

Threshold Transformations

Thresholding is the simplest yet effective method for segmenting images. It involves converting an image from color or grayscale to a binary format, essentially reducing it to just two colors: black and white.

This technique is most commonly used to isolate areas of interest within an image, effectively ignoring the parts that are not relevant to the specific task. It's particularly useful in applications where the distinction between objects and the background is crucial.

In the simplest form of thresholding, each pixel in an image is compared to a predefined threshold value $T$. If the intensity $f(x,y)$ of a pixel is less than $T$, that pixel is turned black (0 value). Conversely, if a pixel's intensity is greater than $T$, it is turned white (255 value). This binary transformation creates a clear distinction between higher and lower intensity values, simplifying the image's content for further analysis or processing.

Python Implementation

Having discussed the concept of threshold transformations, we now apply this technique to a real image using the following code:

# Load an image in grayscale

Im3 = cv2.imread('/content/Image_3.png', cv2.IMREAD_GRAYSCALE)

# Apply the Threshold transformation

_ , Im3_threshold = cv2.threshold(Im3, 25, Im3.max(), cv2.THRESH_BINARY)

# Prepare images for display

images = [Im3, Im3_threshold]

titles = ['Original Image', 'Threshold Transformation']

# Use the plot_images function to display the original and transformed images

plot_images(images, titles, 1, 2, (10, 7))

We first load an image in grayscale from a specified path (/content/Image_3.png). We then apply the threshold transformation using OpenCV's threshold function, the threshold value is set to $25$, and the maximum value to Im3.max(). This means that all pixel values below $25$ are set to $0$ (black), and those above $25$ are set to the maximum pixel value of the image (white). Finally, we apply the plot_images function to display the original and transformed images. The results are shown below:

The original image is the same as in the previous section, but now the transformation has been performed using a threshold function. This resulted in a binary image that represents the skeleton. However, it loses information about the extremities and exhibits poor segmentation in the pelvic and rib areas.

Bonus: Adaptive Threshold Transformations

Adaptive Threshold Transformation is a sophisticated alternative to the basic thresholding technique. While standard thresholding applies a single threshold value across the entire image, adaptive thresholding adjusts the threshold dynamically over different regions of the image. This approach is particularly effective in dealing with images where lighting conditions vary across different areas, leading to uneven illumination.

Adaptive thresholding works by calculating the threshold for a pixel based on a small region around it, commonly employing statistical measures, such as the mean or median. This means that different parts of the image can have different thresholds, allowing for more nuanced and localized segmentation. The method is especially useful in scenarios where the background brightness or texture varies significantly, posing challenges for global thresholding methods.

Adaptive thresholding is widely used in applications such as text recognition, where it helps to isolate characters from a variable background, or in medical imaging, where it can enhance the visibility of features in areas with differing lighting conditions.

Python Implementation

Having discussed the concept of threshold transformations, we now apply this technique to a real image using the following code:

After discussing the theory behind adaptive threshold transformation, we are ready for the practical implementation. We apply this technique to the same image as the previous threshold transformation with the following code:

# Load an image in grayscale

Im3 = cv2.imread('/content/Image_3.png', cv2.IMREAD_GRAYSCALE)

# Apply the Adaptive Threshold transformation

Im3_adapt_threshold = cv2.adaptiveThreshold(Im3, 255, cv2.ADAPTIVE_THRESH_MEAN_C, cv2.THRESH_BINARY, 61,-2)

# Prepare images for display

images = [Im3, Im3_adapt_threshold]

titles = ['Original Image', 'Adaptive Threshold']

# Use the plot_images function to display the original and transformed images

plot_images(images, titles, 1, 2, (10, 7))

We first load an image in grayscale from a specified path (/content/Image_3.png). Then, we apply the adaptive threshold transformation using OpenCV's adaptiveThreshold function. The parameters include a maximum value of $255$, the adaptive method cv2.ADAPTIVE_THRESH_MEAN_C (which uses the mean of the neighborhood area), the threshold type cv2.THRESH_BINARY, a block size of $61$ (determining the size $61 \times 61$ of the neighborhood area), and a constant of $-2$ subtracted from the mean. Finally, we use the plot_images function to display the original and transformed images side by side. The results are shown below:

Unlike the results obtained with a basic thresholding technique, the adaptive threshold transformation allows for the successful segmentation of the complete skeleton by tuning the method's parameters. This approach results in a more detailed and comprehensive visualization of the skeletal structure. From the extremities to the ribs, pelvis, and skull, each part of the skeleton is clearly delineated.